By Veronica Parkes

Ancient Origins

The Maya were a powerful pre-Columbian civilization who thrived between AD 600 – AD 800. They were literate, had a complex language including pictograms, glyphs, and phonetic representations. They even produced books called codices, some of which were reported to detail 800 years of their history. However, scared that the content of these books might interfere with their mission, the mid 16th-century Franciscan missionaries from Spain destroyed almost all of these codices during their systematic conquest and colonization of South America. Today only three or four of these important documents remain but even these provide an invaluable insight into the Mayan world.

The Surviving Maya Codices

For years it was thought that the codices were made from maguey (plant) fiber, but in 1910 it was discovered that they were actually made from the inner bark of fig trees. Written on long strips the codices were then folded up accordion style to be preserved. The surviving Codices contain information about Maya astronomy, astrology, religion, and rituals.

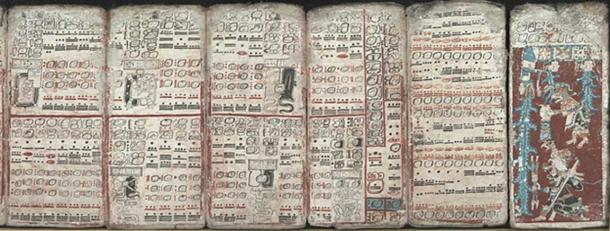

Six sheets of the Dresden Codex (pp. 55-59, 74) depicting eclipses, multiplication tables and the flood (Public Domain)

Three of the codices are named according to the European cities in which they are kept: Dresden, Paris, and Madrid, and a possible fourth is still being reviewed for its authenticity. The codices were probably written no earlier than the 12th-century AD, meaning they were written in the later years of the Maya, but it is possible that they were copied from much earlier books. According to archaeoastronomer Anthony Aveni, the codices were used to set dates for rituals, often linking them to astronomical events. The individual pages in the codices usually depict a deity and include a series of glyphs describing what that deity is doing. These pages also contain lists of numbers that allowed the Maya to predict lunar and solar eclipses, and phases of the moon, and the movements of Mars and Venus. On other pages dates and glyphs are listed that pertain to omens and augury.

Dresden Codex

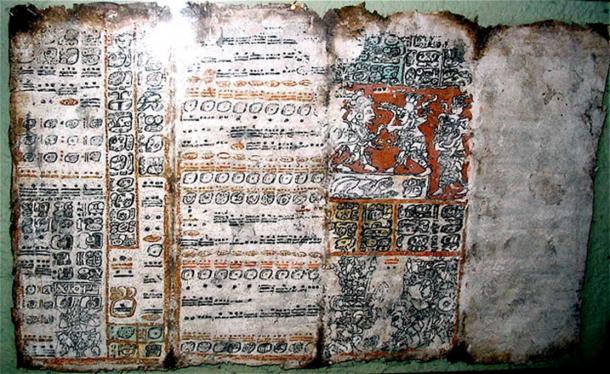

The Dresden Codex is the most complete of the surviving Maya codices. It came to the Royal Library in Dresden in 1739 after it was purchased from a private collector. It was produced by more than eight different scribes and it is believed to have been created sometime between AD 1000 and AD 1200 during the Postclassic Maya period. The codex deals mainly with astronomy as it pertains to the days of the year, calendars, farming, prophecies, etc. There is also a portion of the codex that deals with sickness and medicine. In World War II the Dresden Codex sustained heavy water damage in the Dresden Fire Storms. Therefore, the facsimiles made before the war are used for study as opposed to the original.

Pages of the “Dresden” Maya codex (CC BY 2.0)

Paris Codex

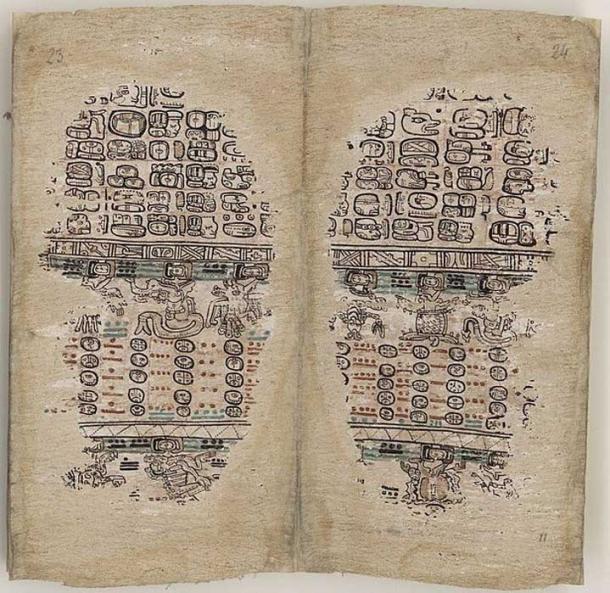

The Paris Codex was said to have been acquired by the Bibliothèque Nationale of Paris in 1832. Its first known replication was a set of drawings by Aglio ca. 1835. While the drawings are now lost, the lithographic prints have been preserved in the Newberry Library of Chicago. Though the Paris Codex was mentioned but a few times over the next 24 years, it did not really make its debut until 1859 when Léon de Rosny was said to have “discovered” it in a box he found in a dusty basket beside a fireplace in an office of the Paris Library. It is not a complete codex, but rather fragments of eleven double-sided pages. It is believed to date from the late Classic or Postclassic period of Maya history. The information found in this codex pertains to ceremonies, astronomy, constellations, and historical information about the Maya gods and spirits.

Pages 23-24 of the Paris Codex, a Postclassic Maya book. (Public Domain)

Madrid Codex

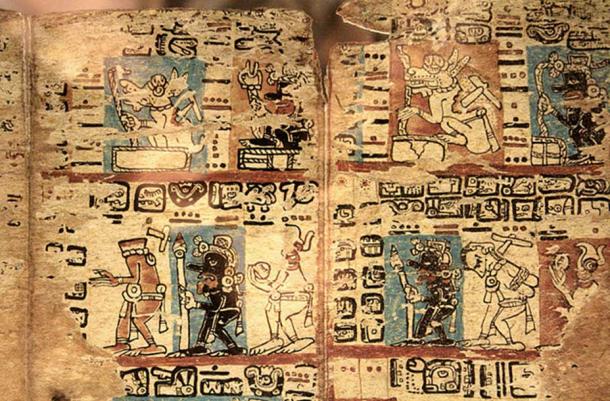

The Madrid Codex was, for some unknown reason, separated into two parts after it reached Europe, and for a while it was considered to be two different codices. The two parts had been called the “Troano” and the “Cortesanius”. The Troano comprised pages 22-56, 78-112 and the Cortesianus pages 1-21, 57-77 of the Madrid Codex. The two halves were finally reunited in 1888. This codex has been dated to the late Postclassic period, ca. AD 1400 , or perhaps even later, this explains its poorly drawn pages. Scholars have found that as many as nine different scribes worked on it. This codex, like the Paris Codex, contains information on the Maya Gods, as well as the rituals associated with the Maya New Year. There is some information on the different days of the year and the Gods associated with them, as well as a section on basic day-to-day Maya activities such hunting and making pottery. The Madrid Codex is now in the Museo de América, in Madrid, Spain.

Madrid Codex. Maya Codex also known as Tro-Cortesianus. Origin unknown, Epoch: Late Postclassic Maya (CC BY SA 3.0)

The Fourth Codex

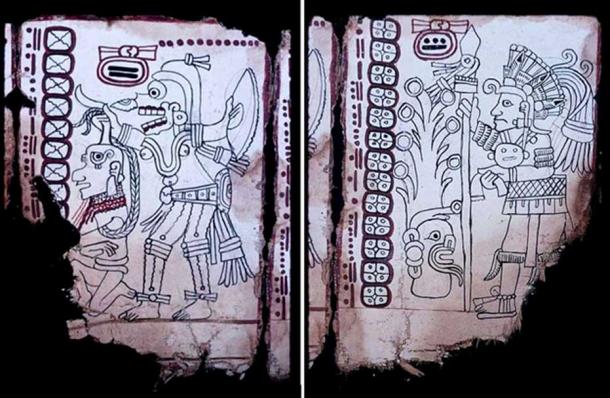

The authenticity of the fourth and most recently discovered codex is still being disputed. The Grolier Codex, now in Mexico City, was not discovered until 1965. It consists of eleven tattered pages of what was most likely once a much larger volume. The discovery of this codex was well documented in Michael Coe’s “Breaking the Maya Code,” in which a Mexican collector, Dr. José Saenz, was brought to Central America and was presented with a bounty of relics that contained the codex. The artifacts were said to have come from a nearby cave. From there Dr. Saenz brought the codex to New York where it was shown by Michael Coe at the Grolier Club in 1971. Currently, the codex sits in a vault in Mexico City. Like the other codices the subject matter deals with astrology.

Right: Grolier Codex, Page 6. Left: Grolier Codex, Page 7 (Public Domain)

Top image: One of the first cultures to have books were the Maya codices written on doubled-over pages and covered by a layer of “stucco”. (CC BY NC 2.0)